|

The Myth Patterns of |

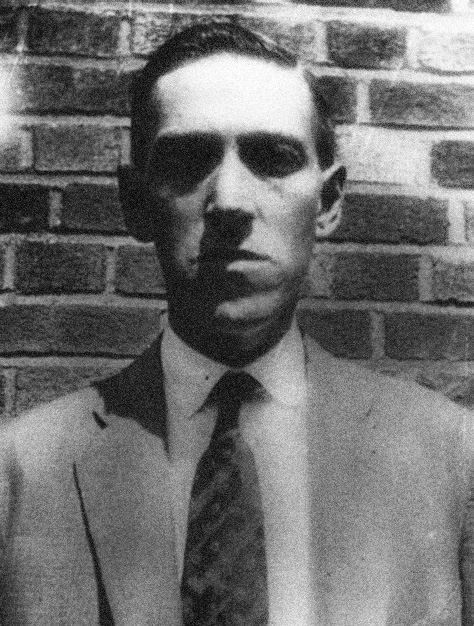

H. P. Lovecraft was a great admirer of Lord Dunsany's book The Gods of Pegāna, which introduced a pantheon of newly-invented gods. Although Lovecraft went on to develop something like a pantheon of his own, he never produced a work like Dunsany's to introduce all his gods. Instead, Lovecraft's "Yog-Sothothery" developed piecemeal, through a process of accretion, with new stories contributing new gods and elder races. In the process, the same beings could be presented in very different ways in different stories. These changes were possible because none of the information is ever presented as definitive. Instead, the stories present various informants whose views are incomplete and possibly even deluded. Even the Necronomicon is presented as an incomplete and doubtful source at best [bolding in all quotes is my own]:

No book had ever really hinted of it [the cult of the Great Old Ones], though the deathless Chinamen said that there were double meanings in the Necronomicon of the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred which the initiated might read as they chose, especially the much-discussed couplet:

“That is not dead which can eternal lie,

And with strange aeons even death may die.”

[HPL Call]

...I started with loathing when told of the monstrous nuclear chaos beyond angled space which the Necronomicon had mercifully cloaked under the name of Azathoth.

[Whisperer]

I found myself faced by names and terms that I had heard elsewhere in the most hideous of connexions—Yuggoth, Great Cthulhu, Tsathoggua, Yog-Sothoth, R’lyeh, Nyarlathotep, Azathoth, Hastur, Yian, Leng, the Lake of Hali, Bethmoora, the Yellow Sign, L’mur-Kathulos, Bran, and the Magnum Innominandum—and was drawn back through nameless aeons and inconceivable dimensions to worlds of elder, outer entity at which the crazed author of the Necronomicon had only guessed in the vaguest way.

[Whisperer]

The Guide knew, as he knew all things, of Carter’s quest and coming, and that this seeker of dreams and secrets stood before him unafraid. There was no horror or malignity in what he radiated, and Carter wondered for a moment whether the mad Arab’s terrific blasphemous hints, and extracts from the Book of Thoth, might not have come from envy and a baffled wish to do what was now about to be done.

[Gates]

The reader could be pardoned for feeling whiplash at the various ways Yog-Sothoth is presented in different stories: as a servitor demon who can be called on to reanimate corpses, as an invader intent on the conquest of Earth, or as a serenely indifferent archetype of all wizards, thinkers, and artists [Case, Dunwich, Gates]. And after reading of the perils posed by deities such as Cthulhu and Yig, it is disorienting at best to encounter worshippers who regard them as benevolent father figures. [Mound]

Given the incomplete and biased nature of the sources presented in Lovecraft's stories, there has even been some question about whether any of Lovecraft's entities should really be considered "gods," or whether they are simply space aliens masquerading as gods for their deluded followers.[fn1] To me, the "gods vs. aliens" distinction seems like a false dichotomy. However, this is not the place to address the issue of terminology. Those beings in Lovecraft's stories, who have immense powers and who also have worshippers, shall be referred to here as "gods." They could also be considered demons, and might have been considered such by some of their votaries.

Overall, Lovecraft's "Yog-Sothothery" comes across less as a single myth-pattern, and more as a loosely related assortment of partially developed myth patterns, each developed on an ad-hoc basis to serve the needs of his latest story. This becomes more clear when you become aware of all the dropped threads in his work: suggestive ideas that were introduced and then never followed up, and never set in clear relation to his other concepts. This shambolic, half-disordered quality to Lovecraft's myths actually works well in the context of his stories. His various "in" references remain suggestive atmospheric hints, rather than prescriptive rules. They open up possibilities, rather than closing them off.

So as we survey Lovecraft's myth patterns, it is best not to expect a definitive, single view of what was going on in his "world." We can, however, identify many of the recurring elements, and outline the relationships that are suggested to exist between them.

Disclaimer about terminology: Lovecraft used the same or similar terms for several distinct groups of beings. To distinguish among the various types of Old Ones in Lovecraft's stories, this article refers to the invisible beings from Dunwich as the Old Ones of Yog-Sothoth; the humanoid race from Mound as the Old Ones of K'n-yan; and the barrel-shaped creatures with starfish heads from Mountains as the Antarctic Old Ones. (Of course, the race from Mountains inhabited more areas than Antarctica, but the alternative of calling them the "crinoid Old Ones" struck me as too obscure.) None of these Old Ones should be confused with the Great Old Ones from Call; nor should the latter be confused with the Great Race [Time] or the Great Ones (Gods of Earth) from the dreamlands stories such as Kadath.[fn2]

Contents

- The Primal Chaos: Who's Calling the Tunes?

- The Great Ones and the Other Gods

- Nodens, the Rogue God

- Cthulhu and Company

- Yog-Sothoth, Reanimator

- Great, Old, Ancient, and Other Gods

- Gods of Good Reputation

- Rhan-Tegoth and the Return of the Old Ones

- Gods of Lost Mnar

- Gods and Devotees

- Factions and Conflicts

- The Hierarchy of Alienness

- The Prolonged of Life

- Imprisoned with the Old Ones

- Déjà Vu of the Future

- Pagan Burrowings

- Concluding Thoughts

The Primal Chaos: Who's Calling the Tunes?

The chief deity in Lovecraft's pantheon is

...that shocking final peril which gibbers unmentionably outside the ordered universe, where no dreams reach; that last amorphous blight of nethermost confusion which blasphemes and bubbles at the centre of all infinity—the boundless daemon-sultan Azathoth, whose name no lips dare speak aloud, and who gnaws hungrily in inconceivable, unlighted chambers beyond time... [Kadath]

The primacy of Azathoth is attested in various works. In Lovecraft's family tree of the elder beings, Azathoth is at the beginning of the chart [Family]. The sonnet "Azathoth" tells us

Here the vast Lord of All in darkness muttered

Things he had dreamed but could not understand,

While near him shapeless bat-things flopped and fluttered

In idiot vortices that ray-streams fanned.

They danced insanely to the high, thin whining

Of a cracked flute clutched in a monstrous paw,

Whence flow the aimless waves whose chance combining

Gives each frail cosmos its eternal law.

[Fungi XXII]

The leading attributes of Azathoth are: he dwells in the center of Chaos; he is "mindless," but dreaming; he is gnawing hungrily; and he gives rise to all the universes, including our own. Also, he is very dangerous to approach. Thus, the violet gas S'ngac warned Kuranes never to approach the central void where Azathoth gnaws hungrily in the dark. [Kadath]

Azathoth is closely associated with the Other Gods or Ultimate Gods.

...the boundless daemon-sultan Azathoth...who gnaws hungrily in inconceivable, unlighted chambers beyond time amidst the muffled, maddening beating of vile drums and the thin, monotonous whine of accursed flutes; to which detestable pounding and piping dance slowly, awkwardly, and absurdly the gigantic ultimate gods, the blind, voiceless, tenebrous, mindless Other Gods... [Kadath]

...the awful voids outside the ordered universe where the daemon-sultan Azathoth gnaws hungrily in chaos amid pounding and piping and the hellish dancing of the Other Gods, blind, voiceless, tenebrous, and mindless... [Kadath]

So the Other Gods seem to form an entourage of sorts for Azathoth. Like him, they are "mindless," but they are a bit more active since they are dancing. Like Azathoth, they are dangerous:

Remember the Other Gods; they are great and mindless and terrible, and lurk in the outer voids. They are good gods to shun. [Kadath]

Some of the Other Gods exist in a larval form in interplanetary and interstellar space:

It was dark when the galley passed betwixt the Basalt Pillars of the West and the sound of the ultimate cataract swelled portentous from ahead. And the spray of that cataract rose to obscure the stars, and the deck grew damp, and the vessel reeled in the surging current of the brink. Then with a queer whistle and plunge the leap was taken, and Carter felt the terrors of nightmare as earth fell away and the great boat shot silent and comet-like into planetary space. Never before had he known what shapeless black things lurk and caper and flounder all through the aether, leering and grinning at such voyagers as may pass, and sometimes feeling about with slimy paws when some moving object excites their curiosity. These are the nameless larvae of the Other Gods, and like them are blind and without mind, and possessed of singular hungers and thirsts. [Kadath]

Unswerving and obedient to the foul legate’s orders, that hellish bird plunged onward through shoals of shapeless lurkers and caperers in darkness, and vacuous herds of drifting entities that pawed and groped and groped and pawed; the nameless larvae of the Other Gods, that are like them blind and without mind, and possessed of singular hungers and thirsts. [Kadath]

A larva is a "distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults" ["Larva," Wikipedia] It is not clear whether the larvae are children of the mature Other Gods, or whether they are spawned directly by Azathoth.

The other key member of Azathoth's circle is "that frightful soul and messenger of infinity’s Other Gods, the crawling chaos Nyarlathotep" [Kadath]. He gives orders on behalf of the Other Gods:

So, Randolph Carter, in the name of the Other Gods I spare you and charge you to serve my will. I charge you to seek that sunset city which is yours, and to send thence the drowsy truant gods for whom the dream-world waits. [Kadath]

Nyarlathotep is intelligent, crafty, and has been known to incarnate in human form [Kadath, Nyarlathotep, Fungi XXI]. As the Black Man of the witch-cult, he helps to waylay humans into signing the book of Azathoth [WitchHouse]. It is not clear whether he is one of the Other Gods, or a servant of theirs, or a composite persona that emerges from the interaction of all of them.

It has been suggested [fn3] that Nyarlathotep actually manipulates and directs Azathoth's creative energy; Lovecraft does not specify whether the flute that "gives each frail cosmos its eternal law" is played by Azathoth or Nyarlathotep [Fungi XXII]. However, I am inclined to think that Azathoth plays the flute himself, since it gives forth "aimless waves whose chance combining / Gives each frail cosmos its eternal law." The key point here is that the flute playing is aimless, and that quality is characteristic of Azathoth rather than the scheming Nyarlathotep.

The Other Gods do not appear in Lovecraft's family tree of the gods [Family], unless possibly the direct offspring of Azathoth in that chart can be considered to be among the Other Gods. However, the chart lists only three names at this level: Nyarlathotep, the Nameless Mist, and Darkness. Lovecraft doesn't specify how many Other Gods there are, but there would seem to be more than three, especially since there are new ones that are still in their larval stage.

Azathoth existed for aeons before creating the Other Gods:

Trembling in waves that golden wisps of nebula made weirdly visible, there rose a timid hint of far-off melody, droning in faint chords that our own universe of stars knows not. And as that music grew, the shantak raised its ears and plunged ahead, and Carter likewise bent to catch each lovely strain. It was a song, but not the song of any voice. Night and the spheres sang it, and it was old when space and Nyarlathotep and the Other Gods were born. [Kadath]

It's worth pointing out that this Azathoth/Other Gods/Nyarlathotep grouping did not appear all at once. Nyarlathotep first appears in the mysterious vignette "Nyarlathotep" in 1920. Here he is identified as the soul of the "ultimate gods," but Azathoth goes unmentioned:

And through this revolting graveyard of the universe the muffled, maddening beating of drums, and thin, monotonous whine of blasphemous flutes from inconceivable, unlighted chambers beyond Time; the detestable pounding and piping whereunto dance slowly, awkwardly, and absurdly the gigantic, tenebrous ultimate gods—the blind, voiceless, mindless gargoyles whose soul is Nyarlathotep. [Nyarlathotep]

Despite the dreamlike quality of the story, and its actual genesis in one of Lovecraft's dreams, it appears to be set in our waking world rather than in the dreamlands.

Azathoth first appears as the title of a brief fragment in 1922, but is not discussed in the text [Azathoth]. The setting is a drab city, evidently in the waking world.

The Other Gods appeared next, in 1921's "The Other Gods." This tale is explicitly set in the dreamlands, but tells us nothing of the nature or habits of the Other Gods, except that they are "gods of the outer hells that guard the feeble gods of earth" [Other]. No mention is made of Azathoth, Nyarlathotep, mindlessness, chaos, flutes, or dancing. Then in 1926, "The Strange High House in the Mist" gives us a passing mention: the bearded host speaks of times "before the gods or even the Elder Ones were born, and when only the other gods came to dance on the peak of Hatheg-Kla in the stony desert near Ulthar, beyond the river Skai" [Mist].

It is in Kadath that Lovecraft first brings these elements together. Here the ultimate gods of the waking world and the Other Gods of dreamland are first identified as the same: "the gigantic ultimate gods, the blind, voiceless, tenebrous, mindless Other Gods..." [emphasis mine] It's an instance where Lovecraft seems to have belatedly identified elements that he originally conceived as being separate. Here we also learn that the ultimate gods/Other Gods are associated with Azathoth, who for the first time is introduced as the mindless peril at the center of chaos. In the process, Nyarlathotep, as the soul of the Other Gods, is also brought into Azathoth's orbit. [Kadath]

The Great Ones and the Other Gods

The humans of the dreamlands worship a group of beings referred to as the Great Ones (not to be confused with the Great Old Ones). They are also known as Earth's gods, the gods of Earth, or the Elder Ones. They are first referenced as a group in 1921's "The Other Gods" [Other].

Atop the tallest of earth’s peaks dwell the gods of earth, and suffer no man to tell that he hath looked upon them. Lesser peaks they once inhabited; but ever the men from the plains would scale the slopes of rock and snow, driving the gods to higher and higher mountains till now only the last remains. When they left their older peaks they took with them all signs of themselves; save once, it is said, when they left a carven image on the face of the mountain which they called Ngranek. [Other]

The leading characteristics of the Great Ones are thus: their unwillingness to be seen by humans, their tendency to withdraw to more remote mountainous places to avoid us, and their nostalgic habit of occasionally revisiting the lesser peaks where they once lived.

In Ulthar, there is a Temple of the Elder Ones:

Carter, the cats being somewhat dispersed by the half-seen zoogs, picked his way directly to the modest Temple of the Elder Ones where the priests and old records were said to be; and once within that venerable circular tower of ivied stone—which crowns Ulthar’s highest hill—he sought out the patriarch Atal, who had been up the forbidden peak Hatheg-Kla in the stony desert and had come down again alive. [Kadath]

In Inganok, there is a grander temple:

On a hill in the centre rose a sixteen-angled tower greater than all the rest and bearing a high pinnacled belfry resting on a flattened dome. This, the seamen said, was the Temple of the Elder Ones, and was ruled by an old high-priest sad with inner secrets. [Kadath]

The only one of Great Ones to be mentioned by name is Nath-Horthath:

...the turquoise temple of Nath-Horthath, where the orchid-wreathed priests told [Kuranes] that there is no time in Ooth-Nargai, but only perpetual youth. [Celephais]

...Carter knew that they were come to the land of Ooth-Nargai and the marvellous city of Celephaïs. ... As it has always been is still the turquoise of Nath-Horthath, and the eighty orchid-wreathed priests are the same who builded it ten thousand years ago. [Kadath]

Though Nath-Horthath is chiefly worshipped in Celephaïs, all the Great Ones are mentioned in diurnal prayers; and the priest was reasonably versed in their moods. [Kadath]

It seems the Great Ones have human-like features, but are possibly of vast size.

...poor Atal babbled freely of forbidden things; telling of a great image reported by travellers as carved on the solid rock of the mountain Ngranek, on the isle of Oriab in the Southern Sea, and hinting that it may be a likeness which earth’s gods once wrought of their own features in the days when they danced by moonlight on that mountain. And he hiccoughed likewise that the features of that image are very strange, so that one might easily recognise them, and that they are sure signs of the authentic race of the gods. [Kadath]

At last, in the fearsome iciness of upper space, he [Carter] came round fully to the hidden side of Ngranek... Stern and terrible shone that face that the sunset lit with fire. How vast it was no mind can ever measure, but Carter knew at once that man could never have fashioned it. It was a god chiselled by the hands of the gods, and it looked down haughty and majestic upon the seeker. Rumour had said it was strange and not to be mistaken, and Carter saw that it was indeed so; for those long narrow eyes and long-lobed ears, and that thin nose and pointed chin, all spoke of a race that is not of men but of gods. [Kadath]

To me, the description seems a bit reminiscent of the stone faces of Easter Island; perhaps Lovecraft had them in mind.

It seems the Great Ones, like the Greek Gods, often mate with humans:

It is known that in disguise the younger among the Great Ones often espouse the daughters of men, so that around the borders of the cold waste wherein stands Kadath the peasants must all bear their blood. This being so, the way to find that waste must be to see the stone face on Ngranek and mark the features; then, having noted them with care, to search for such features among living men. Where they are plainest and thickest, there must the gods dwell nearest; and whatever stony waste lies back of the villages in that place must be that wherein stands Kadath. [Kadath]

All agree that one should never approach the Great Ones:

They might, Atal said, heed a man’s prayer if in good humour; but one must not think of climbing to their onyx stronghold atop Kadath in the cold waste. It was lucky that no man knew where Kadath towers, for the fruits of ascending it would be very grave. Atal’s companion Barzai the Wise had been drawn screaming into the sky for climbing merely the known peak of Hatheg-Kla. With unknown Kadath, if ever found, matters would be much worse; for although earth’s gods may sometimes be surpassed by a wise mortal, they are protected by the Other Gods from Outside, whom it is better not to discuss.

Like Atal in distant Ulthar, he [the high priest in Celephaïs] strongly advised against any attempt to see them; declaring that they are testy and capricious, and subject to strange protection from the mindless Other Gods from Outside, whose soul and messenger is the crawling chaos Nyarlathotep. [Kadath]

Kuranes did not know where Kadath was, or the marvellous sunset city; but he did know that the Great Ones were very dangerous creatures to seek out, and that the Other Gods had strange ways of protecting them from impertinent curiosity. [Kadath]

It is never really explained why the Other Gods protect the Great Ones from being viewed by mortals. There is some suggestion that the Other Gods exert a control over the Great Ones that is not truly benevolent, such as when

...the crawling chaos Nyarlathotep strode brooding into the onyx castle atop unknown Kadath in the cold waste, and taunted insolently the mild gods of earth whom he had snatched abruptly from their scented revels in the marvellous sunset city. [Kadath]

Of course, at that point, Nyarlathotep may have been a bad mood because Randolph Carter had just escaped his trap. But it seems the the Other Ones sometimes do act in response to requests from the Great Ones:

...few had seen the stone face of the god, because it is on a very difficult side of Ngranek, which overlooks only sheer crags and a valley of sinister lava. Once the gods were angered with men on that side, and spoke of the matter to the Other Gods. [Kadath]

There is also the following strange circumstance:

The gugs, hairy and gigantic, once reared stone circles in that wood [the enchanted wood] and made strange sacrifices to the Other Gods and the crawling chaos Nyarlathotep, until one night an abomination of theirs reached the ears of earth’s gods and they were banished to caverns below. [Kadath]

We are not told the nature of the gugs' "abomination," but it may have been one of their "strange sacrifices to the Other Gods." If so, then who banished the gugs? Were the Great Ones able to banish devotees of the Other Gods? Surely one would have expected the Other Gods to protect their devotes. Or did the Great Ones appeal to the Other Gods and complain that the gugs were going too far with their "abominable" devotions?

Whatever the relationship between the Great Ones and the Other Gods, there is a great power imbalance between them. The priests Nasht and Kaman-Thah explain to Carter that other planets have their own dreamlands:

...not only had no man ever been to unknown Kadath, but no man had ever suspected in what part of space it may lie; whether it be in the dreamlands around our world, or in those surrounding some unguessed companion of Fomalhaut or Aldebaran. [Kadath]

However, the scope of the Great Ones' power is strictly limited to earth's dreamland:

From him [Atal] Carter learned many things about the gods, but mainly that they are indeed only earth’s gods, ruling feebly our own dreamland and having no power or habitation elsewhere. [Kadath]

Probably, Atal said, the place [that Carter sought] belonged to his especial dream-world and not to the general land of vision that many know; and conceivably it might be on another planet. In that case earth’s gods could not guide him if they would. [Kadath]

By contrast, the Other Gods live in the center of Chaos with their soul Nyarlathotep and the mindless, dreaming creator Azathoth. Yet the influence of the Other Gods is never far away:

It is understood in the land of dream that the Other Gods have many agents moving among men; and all these agents, whether wholly human or slightly less than human, are eager to work the will of those blind and mindless things in return for the favour of their hideous soul and messenger, the crawling chaos Nyarlathotep. [Kadath]

Nodens, the Rogue God

There is another being who seems to stand somewhat outside the groupings of the Great Ones and the Other Gods. We first encounter the hoary god Nodens in Mist. Though set in the waking world, on the cliffs outside Kingsport, the story records a seeming intrusion into the waking world from the land of dream. The sea mists, it seem, bear dreams from an undersea realm of the Elder Ones:

In the morning mist comes up from the sea by the cliffs beyond Kingsport. White and feathery it comes from the deep to its brothers the clouds, full of dreams of dank pastures and caves of leviathan. And later, in still summer rains on the steep roofs of poets, the clouds scatter bits of those dreams, that men shall not live without rumour of old, strange secrets, and wonders that planets tell planets alone in the night. When tales fly thick in the grottoes of tritons, and conches in seaweed cities blow wild tunes learned from the Elder Ones, then great eager mists flock to heaven laden with lore, and oceanward eyes on the rocks see only a mystic whiteness, as if the cliff’s rim were the rim of all earth, and the solemn bells of buoys tolled free in the aether of faery. [Mist]

In a house on the cliffs lives a man who "had communed with the mists of the sea and the clouds of the sky" for unnumbered years. Speaking to Thomas Olney, the man seems to draw a distinction between at least three classes of divinities, based on their age:

And the day wore on, and still Olney listened to rumours of old times and far places, and heard how the Kings of Atlantis fought with the slippery blasphemies that wriggled out of rifts in ocean’s floor, and how the pillared and weedy temple of Poseidonis is still glimpsed at midnight by lost ships, who know by its sight that they are lost. Years of the Titans were recalled, but the host grew timid when he spoke of the dim first age of chaos before the gods or even the Elder Ones were born, and when only the other gods came to dance on the peak of Hatheg-Kla in the stony desert near Ulthar, beyond the river Skai. [Mist]

It seems that the Other Gods are the oldest, followed by the Elder Ones, then by another group called simply "the gods." The "Elder Ones" are simply another name for the Great Ones of earth's dreamlands. The more recent group of "the gods" are not described, but they may be associated with Atlantis and perhaps with Greece, since the Titans figured in Greek mythology. Possibly all the gods of Greek and Roman mythology fall into this category.

Then Nodens makes his entrance:

And then to the sound of obscure harmonies there floated into that room from the deep all the dreams and memories of earth’s sunken Mighty Ones. And golden flames played about weedy locks, so that Olney was dazzled as he did them homage. Trident-bearing Neptune was there, and sportive tritons and fantastic nereids, and upon dolphins’ backs was balanced a vast crenulate shell wherein rode the grey and awful form of primal Nodens, Lord of the Great Abyss. And the conches of the tritons gave weird blasts, and the nereids made strange sounds by striking on the grotesque resonant shells of unknown lurkers in black sea-caves. Then hoary Nodens reached forth a wizened hand and helped Olney and his host into the vast shell, whereat the conches and the gongs set up a wild and awesome clamour. And out into the limitless aether reeled that fabulous train, the noise of whose shouting was lost in the echoes of thunder. [Mist]

The phrase "earth's sunken Mighty Ones" seems to include figures that European mythologies associate with the ocean: Nodens, Neptune, nereids, and tritons. Unlike the Great Ones of earth's dreamlands, these sea beings allow themselves to be seen by a mortal man, Thomas Olney. The Other Gods never intervene to prevent Olney from seeing them. But the viewing of them is not without cost, for thereafter Olney seems to have lost his soul, and to spend the remainder of his life in a placid, zombie-like existence:

And at noon elfin horns rang over the ocean as Olney, dry and light-footed, climbed down from the cliffs to antique Kingsport with the look of far places in his eyes. He could not recall what he had dreamed in the sky-perched hut of that still nameless hermit... [The] Terrible Old Man...afterward mumbled queer things in his long white beard; vowing that the man who came down from that crag was not wholly the man who went up, and that somewhere under that grey peaked roof, or amidst inconceivable reaches of that sinister white mist, there lingered still the lost spirit of him who was Thomas Olney.

And ever since that hour, through dull dragging years of greyness and weariness, the philosopher has laboured and eaten and slept and done uncomplaining the suitable deeds of a citizen. Not any more does he long for the magic of farther hills, or sigh for secrets that peer like green reefs from a bottomless sea. The sameness of his days no longer gives him sorrow, and well-disciplined thoughts have grown enough for his imagination. [Mist]

We learn more of Nodens in Kadath when Carter recruits the night-gaunts to assist his quest:

[Carter] had met those silent, flitting, and clutching creatures before; those mindless guardians of the Great Abyss whom even the Great Ones fear, and who own not Nyarlathotep but hoary Nodens as their lord. For they were the dreaded night-gaunts, who never laugh or smile because they have no faces, and who flop unendingly in the dark betwixt the Vale of Pnath and the passes to the outer world. [Kadath]

[Carter] spoke, too, of the things he had learnt concerning night-gaunts from the frescoes in the windowless monastery of the high-priest not to be described; how even the Great Ones fear them, and how their ruler is not the crawling chaos Nyarlathotep at all, but hoary and immemorial Nodens, Lord of the Great Abyss. [Kadath]

And even were unexpected things to come from the Other Gods, who are prone to oversee the affairs of earth’s milder gods, the night-gaunts need not fear; for the outer hells are indifferent matters to such silent and slippery flyers as own not Nyarlathotep for their master, but bow only to potent and archaic Nodens. [Kadath]

Unlike the Great Ones, Nodens does not submit to Nyarlathotep and the Other Gods. Further, the Great Ones fear Noden's followers, the night-gaunts. Apparently the Great Ones are not confident that the Other Gods can protect them from the night-gaunts.

Two other aspects of Nodens are noteworthy. First, he is very old; every mention of his name is accompanied by an adjective such as archaic, hoary, or immemorial. Perhaps the implication is that Nodens is older than the Great Ones. Secondly, Nodens is the lord of the Great Abyss. Recall that the Great Ones prefer to play on high mountain peaks. Nodens, as Lord of the Great Abyss, could be considered to be their opposite. But what is the Great Abyss? We learn that steps lead down to the Great Abyss from Sarkomand, a ruined city in a little-inhabited part of the dreamlands:

Indubitably that primal city was no less a place than storied Sarkomand, whose ruins had bleached for a million years before the first true human saw the light, and whose twin titan lions guard eternally the steps that lead down from dreamland to the Great Abyss. [Kadath]

Gates to the abyss are "guarded by flocks of night-gaunts." The Great Abyss is also home to "the ghouls’ black kingdom." Though Nodens is the Lord of the Great Abyss, the ghouls are not his followers, because "ghouls have no masters." However, they are "bound by solemn treaties" with Noden's followers, the night-gaunts.

The Nodens in Kadath seems to have mutated a bit from his appearance in Mist, where he appeared as an ocean god, and the Great Abyss was evidently a reference to the depths of the sea. In Kadath, his watery associations go totally unmentioned. It's an example where Lovecraft places one of his existing creations in a different context and shows us a new aspect that was previously unsuspected.

Ultimately Carter's army of ghouls and night-gaunts is easily defeated by Nyarlathotep:

Randolph Carter had hoped to come into the throne-room of the Great Ones with poise and dignity, flanked and followed by impressive lines of ghouls in ceremonial order, and offering his prayer as a free and potent master among dreamers. He had known that the Great Ones themselves are not beyond a mortal’s power to cope with, and had trusted to luck that the Other Gods and their crawling chaos Nyarlathotep would not happen to come to their aid at the crucial moment, as they had so often done before when men sought out earth’s gods in their home or on their mountains. And with his hideous escort [Carter] had half hoped to defy even the Other Gods if need were, knowing as he did that ghouls have no masters, and that night-gaunts own not Nyarlathotep but only archaick Nodens for their lord.

But now he saw that supernal Kadath in its cold waste is indeed girt with dark wonders and nameless sentinels, and that the Other Gods are of a surety vigilant in guarding the mild, feeble gods of earth. Void as they are of lordship over ghouls and night-gaunts, the mindless, shapeless blasphemies of outer space can yet control them when they must; so that it was not in state as a free and potent master of dreamers that Randolph Carter came into the Great Ones’ throne-room with his ghouls. Swept and herded by nightmare tempests from the stars, and dogged by unseen horrors of the northern waste, all that army floated captive and helpless in the lurid light, dropping numbly to the onyx floor when by some voiceless order the winds of fright dissolved.

Nodens is not present at this scene, so it doesn't constitute a direct smackdown between him and Nyarlathotep. But to the extent that Nyarlathotep makes short work of Noden's followers, it seems implied that Nodens is actually a lesser power than the Other Gods.

There is some wiggle room here, though. For Carter ultimately escapes from Nyarlathotep's trap. And Nodens seems to assist his escape, at least as a cheerleader:

There were gods and presences and wills; beauty and evil, and the shrieking of noxious night robbed of its prey. For through the unknown ultimate cycle had lived a thought and a vision of a dreamer’s boyhood, and now there were re-made a waking world and an old cherished city to body and to justify these things. Out of the void S’ngac the violet gas had pointed the way, and archaic Nodens was bellowing his guidance from unhinted deeps.

Stars swelled to dawns, and dawns burst into fountains of gold, carmine, and purple, and still the dreamer fell. Cries rent the aether as ribbons of light beat back the fiends from outside. And hoary Nodens raised a howl of triumph when Nyarlathotep, close on his quarry, stopped baffled by a glare that seared his formless hunting-horrors to grey dust. Randolph Carter had indeed descended at last the wide marmoreal flights to his marvellous city, for he was come again to the fair New England world that had wrought him.

Ultimately though, Lovecraft presents this escape not as a triumph of good over evil, but a triumph of beauty over evil. Randolph Carter is saved by his idealized memories of his boyhood. S'ngac and Nodens only pointed the way.

One issue that Lovecraft never directly addresses is why Nyarlathotep opposes Carter's quest. Carter seeks his briefly-glimpsed, fabulous sunset city, and we learn that the Great Ones have taken up residence there. So you could argue that Nyarlathotep is simply enforcing the Other God's usual policy of "protecting" the Great Ones from being seen by mortals. But once Carter escapes, Nyarlathotep abruptly snatches the Great Ones back from the sunset city to Kadath. If Nyarlathotep was going to bring the Great Ones back to Kadath anyway, why would he oppose Carter's search for the sunset city?

It seems that one of Nyarlathotep's duties is to capture souls for Azathoth. Perhaps Azathoth literally eats souls; we know he "gnaws shapeless and ravenous." By pretending to assist Carter's quest, Nyarlathotep gets Carter to mount the shantak that will take him straight to the ultimate chaos. We see this role for Nyarlathotep again later in WitchHouse, where as the Black Man, he tries to entice Walter Gilman to sign the Book of Azathoth.

There's also an intriguing parallel between Carter and Azathoth, since both are dreamers. In Fungi XXII, we learn of Azathoth that "the vast Lord of All in darkness muttered / Things he had dreamed but could not understand." Azathoth's idiot dreams give rise to the cosmos; Carter's dreams create the fabulous sunset city, which beguiles even the Great Ones. Unlike Azathoth, Carter has an intellect, with understanding and goals. But he is not completely master of his own dreams. No sooner has he dreamed of the sunset city than it is taken from him by the Great Ones, perhaps at the behest of the Other Gods. Ultimately his salvation lies not in dreams, which are irredeemably tainted with Azathoth's chaos, but in a return to the childlike quality with which he once experienced his own home town.

Cthulhu and Company

It is in Call [1926] that we first learn of the cult of dread Cthulhu and the Great Old Ones, who eventually serve as the center of a significant cluster of related beings and alien races in Lovecraft's work. The Great Old Ones, it seems, "lived ages before there were any men, and...came to the young world out of the sky."

These beings were far different from native Earth life. According to the cultist named Castro, "These Great Old Ones...were not composed altogether of flesh and blood. They had shape...but that shape was not made of matter." No man had ever seen them. Also, Castro refused to say how large they were.

At one time, they ruled over the earth:

There had been aeons when [the Great Old Ones] ruled on the earth, and They had had great cities. Remains of Them...were still to be found as Cyclopean stones on islands in the Pacific.

However, "they all died vast epochs of time before men came..." Their downfall was due to changes in "the stars":

When the stars were right, They could plunge from world to world through the sky; but when the stars were wrong, They could not live.

When the stars went wrong, a being named Cthulhu was able to save the Great Old Ones:

But although They no longer lived, They would never really die. They all lay in stone houses in Their great city of R’lyeh, preserved by the spells of mighty Cthulhu...

The relationship between Cthulhu and the Great Old Ones is not clearly explained. However, it appears that he is one of the Great Old Ones, and is the only one of them whose appearance is known:

The carven idol was great Cthulhu, but none might say whether or not the others were precisely like him.

These Great Old Ones...had shape—for did not this star-fashioned image [of Cthulhu] prove it?

It appears that there were images of the Great Old Ones at some time in the past:

They had, indeed, come themselves from the stars, and brought Their images with Them.

Presumably these images are now lost or hidden, since no one knows what they look like anymore.

For a few reasons, we can infer that Cthulhu is the most powerful of the Great Old Ones. For one thing, Cthulhu cast the spells that preserved the whole group. Without his help, it seems the rest of the Great Old Ones would have died. Also, he is referred to as "the great priest" and he is expected to rule over Earth when the Great Old Ones return.

The Great Old Ones are omniscient, and communicate with each other telepathically. At one time, they were able to communicate with humans through our dreams:

They knew all that was occurring in the universe, but Their mode of speech was transmitted thought. Even now They talked in Their tombs. When, after infinities of chaos, the first men came, the Great Old Ones spoke to the sensitive among them by moulding their dreams; for only thus could Their language reach the fleshly minds of mammals.

Those [Great] Old Ones were gone now, inside the earth and under the sea; but their dead bodies had told their secrets in dreams to the first men, who formed a cult which had never died.

The chant meant only this: “In his house at R’lyeh dead Cthulhu waits dreaming.”

However, communication was cut off when the Great Old Ones' city of R'lyeh sank:

In the elder time chosen men had talked with the entombed Old Ones in dreams, but then something had happened. The great stone city R’lyeh, with its monoliths and sepulchres, had sunk beneath the waves; and the deep waters, full of the one primal mystery through which not even thought can pass, had cut off the spectral intercourse. But memory never died, and high-priests said that the city would rise again when the stars were right.

Meanwhile, it appears that the Great Old Ones can only communicate with humanity through certain intermediaries, whom the cultists are reluctant to discuss.

Meanwhile no more must be told. There was a secret which even torture could not extract. Mankind was not absolutely alone among the conscious things of earth, for shapes came out of the dark to visit the faithful few. But these were not the Great Old Ones.

All denied a part in the ritual murders, and averred that the killing had been done by Black Winged Ones which had come to them from their immemorial meeting-place in the haunted wood.

Then came out of the earth the black spirits of earth, mouldy and shadowy, and full of dim rumours picked up in caverns beneath forgotten sea-bottoms. But of them old Castro dared not speak much. He cut himself off hurriedly, and no amount of persuasion or subtlety could elicit more in this direction.

The cultists expect Cthulhu and the Great Old Ones to return some day, "when the stars had come round again to the right positions in the cycle of eternity." Even when the stars are right again, Cthulhu will be dependent on his cult followers to set him free:

But at that time some force from outside must serve to liberate Their bodies. The spells that preserved Them intact likewise prevented Them from making an initial move, and They could only lie awake in the dark and think whilst uncounted millions of years rolled by.

The cult expects Cthulhu to rule the earth after his return:

That cult would never die till the stars came right again, and the secret priests would take great Cthulhu from His tomb to revive His subjects and resume His rule of earth.

They worshipped, so they said, the Great Old Ones who lived ages before there were any men, and who came to the young world out of the sky... This was that cult, and the prisoners said it had always existed and always would exist, hidden in distant wastes and dark places all over the world until the time when the great priest Cthulhu...should rise and bring the earth again beneath his sway.

Great Old Ones and Cthulhu Spawn

This account of Cthulhu and the Great Old Ones gets significantly muddied in Mountains [1931]. Professors Lake and Dyer both identify the crinoid Old Ones of Antarctica with the Great Old Ones:

How it could have undergone its tremendously complex evolution on a new-born earth in time to leave prints in Archaean rocks was so far beyond conception as to make Lake whimsically recall the primal myths about Great Old Ones who filtered down from the stars and concocted earth-life as a joke or mistake...

They were the makers and enslavers of that life, and above all doubt the originals of the fiendish elder myths which things like the Pnakotic Manuscripts and the Necronomicon affrightedly hint about. They were the Great Old Ones that had filtered down from the stars when earth was young—the beings whose substance an alien evolution had shaped, and whose powers were such as this planet had never bred.

The Professors are clearly either mistaken, or using the term "Great Old Ones" in a different sense than it was used in Call. The Antarctic Old Ones were never trapped in sunken R'lyeh. Indeed, they fought a war against octopoid beings identified as Cthulhu's spawn:

Another race—a land race of beings shaped like octopi and probably corresponding to the fabulous pre-human spawn of Cthulhu—soon began filtering down from cosmic infinity and precipitated a monstrous war which for a time drove the Old Ones wholly back to the sea—a colossal blow in view of the increasing land settlements. Later peace was made, and the new lands were given to the Cthulhu spawn whilst the Old Ones held the sea and the older lands. ... From then on, as before, the antarctic remained the centre of the Old Ones’ civilisation, and all the discoverable cities built there by the Cthulhu spawn were blotted out. Then suddenly the lands of the Pacific sank again, taking with them the frightful stone city of R’lyeh and all the cosmic octopi... [Mountains]

Are the Cthulhu spawn the same as the Great Old Ones? They are, at least, associated with Cthulhu. But the sequence of events seems inconsistent. In Mountains, the Cthulhu spawn are defeated when R'lyeh sinks. In Call, Cthulhu imprisons himself and the other Great Old Ones because the stars have changed, and R'lyeh doesn't sink until later. The timing of R'lyeh's sinking is also vastly different in the two accounts. In Mountains, R'lyeh sinks sometime prior to the dinosaur era, when the crinoid Old Ones found "the great reptiles proved highly tractable." In Call, R'lyeh does not sink until much later, when humanity exists, and the sinking cuts off the telepathic dream communication between Cthulhu and the early human cultists.

Of course, all the information is incomplete and is related by unreliable sources. The Cthulhu cultists relate an oral tradition. Prof. Dyer and his team reconstruct the history of the crinoid Old Ones, and their war with the Cthulhu spawn, by inspecting wall carvings, but without actually being able to read any of the Old Ones' writing. Also, it seems likely that R'lyeh has sunken and risen on multiple occasions, just as it did again briefly in 1925.

If the Cthulhu spawn and the Great Old Ones are one and the same, then it seems Dyer misunderstood the events that lead to their captivity, thinking that it resulted from R'lyeh's sinking when really it was caused previously by the changes in "the stars." If Cthulhu spawn and the Great Old Ones are different, then it is possible that the Cthulhu spawn were still active on Earth's surface long after Cthulhu and the Great Old Ones went into hibernation.

The Daughter of Cthulhu

Another type of Cthulhu spawn crops up in Medusa [1930]: Marceline Bedard, who styles herself Tanit-Isis, the leader of a cult of decadents in Paris. She appears human, except for her profusion of lush, restless black hair that betrays her true nature as "the thing from which the first dim legends of Medusa and the Gorgons had sprung." A painting by her devotee Frank Marsh reveals her origins in ancient R'lyeh:

But the scene wasn’t Egypt—it was behind Egypt; behind even Atlantis; behind fabled Mu, and myth-whispered Lemuria. It was the ultimate fountain-head of all horror on this earth, and the symbolism shewed only too clearly how integral a part of it Marceline was. I think it must be the unmentionable R’lyeh, that was not built by any creatures of this planet—the thing Marsh and Denis used to talk about in the shadows with hushed voices. In the picture it appears that the whole scene is deep under water—though everybody seems to be breathing freely.

Her husband Denis de Russy understands when he first sees the picture:

The minute I saw it I understood what—she—was, and what part she played in the frightful secret that has come down from the days of Cthulhu and the Elder Ones—the secret that was nearly wiped out when Atlantis sank, but that kept half alive in hidden traditions and allegorical myths and furtive, midnight cult-practices...It was the old, hideous shadow that philosophers never dared mention—the thing hinted at in the Necronomicon and symbolised in the Easter Island colossi.

After Marceline's death, her servant Sophonisba reveals that Marceline was a child of Cthulhu:

Iä! Iä! Shub-Niggurath! Ya-R’lyeh! N’gagi n’bulu bwana n’lolo! Ya, yo, pore Missy Tanit, pore Missy Isis! Marse Clooloo, come up outen de water an’ git yo chile—she done daid! She done daid! De hair ain’ got no missus no mo’, Marse Clooloo.

If Marceline was literally a child of Cthulhu, it seems surprising that she looks human. Also noteworthy is that the painting depicts Marceline as being underwater in R'lyeh, thus implying that she is amphibious. Remember there is nothing to imply that Cthulhu or his spawn are water dwellers. In Cthulhu's era, R'lyeh had not yet sunk.

The painting of Marceline also gives a glimpse of some creatures who may have resided with her in R'lyeh:

The blasphemies that lurk and leer and hold a Witches’ Sabbat with that woman as a high-priestess! The black shaggy entities that are not quite goats—the crocodile-headed beast with three legs and a dorsal row of tentacles—and the flat-nosed aegipans dancing in a pattern that Egypt’s priests knew and called accursed!

Dagon, Hydra, and the Deep Ones

Oddly, more underwater followers are introduced for Cthulhu in Innsmouth [1931]. There we learn of the Deep Ones, an aquatic race that looks like a cross between humans and frogs or fish. They like to interbreed with humans, and the hybrid offspring start out looking human but gradually become more frog-fishy until they swim off to sea. Once the transformation is complete, they are potentially immortal, like the Deep Ones themselves: "Them things never died excep’ they was kilt violent."

The link between the Deep Ones and Cthulhu is not explained, but it is clear that the Innsmouth cultists who consort with the Deep Ones are also followers of Cthulhu. For example, Zadok Allen lapses into the Cthulhu chant (Ph’nglui, etc.) when excited, and the narrator also exclaims Cthulhu fhtagn! when he contemplates joining his Deep One cousins in the sea. And when the narrator predicts that the Deep Ones will return, he says

...they would rise again for the tribute Great Cthulhu craved. It would be a city greater than Innsmouth next time.

It turns out that the Deep Ones have the habit of requiring humans to be given to them as sacrifices. The Deep Ones may simply enjoy eating humans, but perhaps they actually offer the humans to Great Cthulhu, and this is the "tribute" that he craves.

Along with Cthulhu, the Innsmouth cult also honors two figures called Father Dagon and Mother Hydra. Dagon also figures in the name of their cult, the Esoteric Order of Dagon. It seems that Dagon and Hydra are the ultimate ancestors of the Deep Ones:

All in the band of the faithful—Order o’ Dagon—an’ the children shud never die, but go back to the Mother Hydra an’ Father Dagon what we all come from onct...

Which means that Dagon and Hydra might also be the ancestors of humanity:

Seems that human folks has got a kind o’ relation to sech water-beasts—that everything alive come aout o’ the water onct, an’ only needs a little change to go back agin.

We learn nothing more about Hydra, but there are a few small clues about Dagon. In the Old Testament, Dagon is worshipped by the Philistines. Zadok Allen associates Dagon with pagan figures who are regarded as enemies of the Christian God:

Dagon an’ Ashtoreth—Belial an’ Beëlzebub—Golden Caff an’ the idols o’ Canaan an’ the Philistines—Babylonish abominations...

Dagon also apparently figures in the much earlier story Dagon [1917]. There, a sailor finds himself on an island composed of sea floor that has suddenly been thrust up to the surface. The sailor sees an obelisk carved with figures that sound much like the Deep Ones in Innsmouth:

Grotesque beyond the imagination of a Poe or a Bulwer, they were damnably human in general outline despite webbed hands and feet, shockingly wide and flabby lips, glassy, bulging eyes, and other features less pleasant to recall. [Dagon]

However, this species seems much very larger:

Curiously enough, they seemed to have been chiselled badly out of proportion with their scenic background; for one of the creatures was shewn in the act of killing a whale represented as but little larger than himself. [Dagon]

In Innsmouth, the Deep One/human hybrids seem no larger than ordinary humans. It is conceivable that the full-blooded Deep Ones are larger. Alternatively, there may be multiple races of Deep Ones of varying sizes, or they may continue growing forever like lobsters, so that the oldest specimens attain to gigantic stature. The sailor in Dagon sees such a gigantic creature:

Vast, Polyphemus-like, and loathsome, it darted like a stupendous monster of nightmares to the monolith, about which it flung its gigantic scaly arms, the while it bowed its hideous head and gave vent to certain measured sounds. [Dagon]

Polyphemus was a one-eyed giant in Greek mythology, but we are not explicitly told if the figure in Dagon has one eye or more. At any rate, the creature seems to be performing some kind of worship. It might be a Deep One that is worshipping Dagon, or it might be Dagon himself, performing worship to Cthulhu.

That almost completes the catalog of Cthulhu's aquatic allies. In Innsmouth it is hinted that the Deep Ones have an alliance with the shoggoths, who are capable of living underwater. But we will present more about that relationship anon.

Yog-Sothoth, Reanimator

The multifaceted Yog-Sothoth appears first in 1927's Case of Charles Dexter Ward. In this story, he appears to be a sort of demon who is conjured by Joseph Curwen and his confederates, Simon Orne and Edward Hutchinson, to do their bidding. Curwen relates:

I laste Night strucke on ye Wordes that bringe up YOGGE-SOTHOTHE, and sawe for ye firste Time that fface spoke of by Ibn Schacabac in ye——. And IT said, that ye III Psalme in ye Liber-Damnatus holdes ye Clauicle. With Sunne in V House, Saturne in Trine, drawe ye Pentagram of Fire, and saye ye ninth Uerse thrice. This Uerse repeate eache Roodemas and Hallow’s Eue; and ye Thing will breede in ye Outside Spheres.

And of ye Seede of Olde shal One be borne who shal looke Backe, tho’ know’g not what he seekes. [Case]

Apparently Curwen summons up Yog-Sothoth and sees his face. Then Yog-Sothoth provides Curwen with a significant spell. In the event of Curwen's unexpected death, this spell will ensure that one of Curwen's descendants will eventually perform the rites that bring Curwen back from the dead.

Yog-Sothoth also figures in the spells that Curwen uses to raise the dead from their "essential saltes" and to dismiss them afterwards.

☊ Y’AI ‘NG’NGAH, |

☋ OGTHROD AI’F |

Unfortunately, we never learn the full scope of Curwen's ambitions, or the exact role that Yog-Sothoth was expected to play. At first it appears that Curwen, Orne, and Hutchinson are merely trying to accumulate knowledge and power by reanimating and questioning wizards and scientists of past times.

A hideous traffick was going on among these nightmare ghouls, whereby illustrious bones were bartered with the calm calculativeness of schoolboys swapping books; and from what was extorted from this centuried dust there was anticipated a power and a wisdom beyond anything which the cosmos had ever seen concentrated in one man or group.

Charles Dexter Ward learns, however, that something much larger is at stake; as he writes to Dr. Willett:

Upon us depends more than can be put into words — all civilisation, all natural law, perhaps even the fate of the solar system and the universe. I have brought to light a monstrous abnormality, but I did it for the sake of knowledge. Now for the sake of all life and Nature you must help me thrust it back into the dark again... So come quickly if you wish to see me alive and hear how you may help to save the cosmos from stark hell.

It is never stated whether Yog-Sothoth is the agent that forms such an extreme threat to our cosmos. Curwen, Orne, and Hutchinson include references to various beings in the salutations and closings in their letters:

My honour’d Antient ffriende, due Respects and earnest Wishes to Him whom we serve for yr eternall Power.

Sir, I am yr olde and true ffriend and Servt. in Almousin-Metraton.

Josephus C.

Brother in Almousin-Metraton:

...

Yogg-Sothoth Neblod Zin

Simon O.

Nephren-Ka nai Hadoth

Edw: H.

In European magical lore, Almousin and Metraton were two angels. It is possible that the conspirators were using Almousin-Metraton as an alternate name for Yog-Sothoth. On the other hand, Nephren-Ka is an Egyptian pharaoh first referenced in Outsider. Nephren-Ka could hardly be a synonym for Yog-Sothoth, though he could possibly have been one of Yog-Sothoth's prominent devotees.

There are indications that Curwen et al are messing with powers beyond their control; so Orne writes to Curwen:

I rejoice that you traffick not so much with Those Outside; for there was ever a Mortall Peril in it, and you are sensible what it did when you ask’d Protection of One not dispos’d to give it.

[Letter from Edward Hutchinson to Joseph Curwen]

But I wou’d have you Observe what was tolde to us aboute tak’g Care whom to calle up, for you are Sensible what Mr. Mather writ in ye Magnalia of——, and can judge how truely that Horrendous thing is reported.

[Letter from Jebediah Orne to Joseph Curwen]

I say to you againe, doe not call up Any that you can not put downe; by the Which I meane, Any that can in Turne call up somewhat against you, whereby your Powerfullest Devices may not be of use. Ask of the Lesser, lest the Greater shall not wish to Answer, and shall commande more than you.

[Letter from Jebediah Orne to Joseph Curwen]

Curwen may have made this very mistake when the raiding party arrived at his house:

In the light of this passage, and reflecting on what last unmentionable allies a beaten man might try to summon in his direst extremity, Charles Ward may well have wondered whether any citizen of Providence killed Joseph Curwen.

But once again, there is no indication whether the being that he called up in that last extremity was Yog-Sothoth. Possibly Curwen called up something that was lurking underground:

I am ty’d up in Shippes and Goodes, and cou’d not doe as you did, besides the Whiche my ffarme at Patuxet hath under it What you Knowe, that wou’d not waite for my com’g Backe as an Other.

[Letter from Joseph Curwen to Simon Orne]

It will be ripe in a yeare’s time to have up ye Legions from Underneath, and then there are no Boundes to what shal be oures. ...

[Letter from Edward Hutchinson to Joseph Curwen]

Yog-Sothoth and the Old Ones

In Dunwich we encounter a modern backwoods family of Yog-Sothoth devotees, headed by Old Whateley. We learn the ultimate goal of the cultists is to bring about the return of certain beings associated with Yog-Sothoth, who are called the Old Ones. These Old Ones are hidden from us in some sort of state or location that is not space as we know it:

Not in the spaces we know, but between them, They walk serene and primal, undimensioned and to us unseen.

Their hand is at your throats, yet ye see Them not; and Their habitation is even one with your guarded threshold.

Long ago, the Old Ones were in possession of Earth:

“Nor is it to be thought,” ran the text as Armitage mentally translated it, “that man is either the oldest or the last of earth’s masters, or that the common bulk of life and substance walks alone...”

He [Yog-Sothoth] knows where the Old Ones broke through of old...

Kadath in the cold waste hath known Them, and what man knows Kadath? The ice desert of the South and the sunken isles of Ocean hold stones whereon Their seal is engraven, but who hath seen the deep frozen city or the sealed tower long garlanded with seaweed and barnacles?

The Old Ones seem to be immortal:

The Old Ones were, the Old Ones are, and the Old Ones shall be.

The Old Ones are planning to return and take over again:

Man rules now where They ruled once; They shall soon rule where man rules now. After summer is winter, and after winter summer. They wait patient and potent, for here shall They reign again.

He [Dr. Armitage] would shout that the world was in danger, since the Elder Things wished to strip it and drag it away from the solar system and cosmos of matter into some other plane or phase of entity from which it had once fallen, vigintillions of aeons ago.

Meanwhile, the Old Ones are sometimes able to visit Earth temporarily, when summoned by their worshippers:

They walk ... in lonely places where the Words have been spoken and the Rites howled through at their Seasons.

...they cannot take body without human blood.

The Old Ones are invisible to us:

...no one can behold Them as They tread.

They bend the forest and crush the city, yet may not forest or city behold the hand that smites.

But they can be detected by their foul smell.

By Their smell can men sometimes know Them near...

As a foulness shall ye know Them.

They can also be detected by noises on the wind, or from underground:

The wind gibbers with Their voices, and the earth mutters with Their consciousness.

Sometimes the Old Ones mate with human females, who give birth to hybrid beings:

...of Their semblance can no man know, saving only in the features of those They have begotten on mankind; and of those are there many sorts, differing in likeness from man’s truest eidolon to that shape without sight or substance which is Them.

Yog-Sothoth has some special role to play in enabling the return of the Old Ones:

Yog-Sothoth knows the gate. Yog-Sothoth is the gate. Yog-Sothoth is the key and guardian of the gate.

Yog-Sothoth is the key to the gate, whereby the spheres meet.

Past, present, future, all are one in Yog-Sothoth. He knows where the Old Ones broke through of old, and where They shall break through again.

Wilbur Whateley and his unnamed brother are the half-breed children of Yog-Sothoth and Lavinia Whateley. Wilbur's brother is more like the Old Ones than Wilbur is, and so is normally invisible:

That upstairs more ahead of me than I had thought it would be, and is not like to have much earth brain.

That upstairs looks it will have the right cast. I can see it a little when I make the Voorish sign or blow the powder of Ibn Ghazi at it, and it is near like them at May-Eve on the Hill. The other face may wear off some.

Wilbur is expected to perform various rituals to open the gates to Yog-Sothoth:

[Old Whateley, talking to Wilbur:] Open up the gates to Yog-Sothoth with the long chant that ye’ll find on page 751 of the complete edition...

“Today learned the Aklo for the Sabaoth,” it [Wilbur's diary] ran, “which did not like, it being answerable from the hill and not from the air...”

After the gates are open, apparently Yog-Sothoth and the Old Ones will make Wilbur's brother multiply:

“Feed it reg’lar, Willy, an’ mind the quantity; but dun’t let it grow too fast fer the place, fer ef it busts quarters or gits aout afore ye opens to Yog-Sothoth, it’s all over an’ no use. Only them from beyont kin make it multiply an’ work... Only them, the old uns as wants to come back...”

Wilbur, probably with help from his brother, plans to destroy all earthly life:

Grandfather kept me saying the Dho formula last night, and I think I saw the inner city at the 2 magnetic poles. I shall go to those poles when the earth is cleared off, if I can’t break through with the Dho-Hna formula when I commit it. They from the air told me at Sabbat that it will be years before I can clear off the earth, and I guess grandfather will be dead then, so I shall have to learn all the angles of the planes and all the formulas between the Yr and the Nhhngr.

I wonder how I shall look when the earth is cleared and there are no earth beings on it. He that came with the Aklo Sabaoth said I may be transfigured, there being much of outside to work on.

Apparently at some point, the Old Ones will be able to take bodily form without needing human blood. Otherwise, it wouldn't make sense for Wilbur to kill off all earth life.

What happens to the Old Ones' human devotees at this point? It is possible that the Old Ones will make an exception and allow them to live in some form. But given Wilbur's callous sacrifice of his own mother Lavinia, it seems likely that the Old Ones regard all humans as ultimately disposable.

Finally, according to Dr. Armitage, the plan was "wipe out the human race and drag the earth off to some nameless place for some nameless purpose."

So, is the Yog-Sothoth of "The Dunwich Horror" consistent with that of The Case of Charles Dexter Ward? Quite possibly. Although Curwen and his friends were invoking Yog-Sothoth to reanimate dead people, they clearly were also engaged in some greater scheme; Ward saw them as a threat to "all civilisation, all natural law, perhaps even the fate of the solar system and the universe." Perhaps they were attempting to open the gates to Yog-Sothoth so the Old Ones could return.

One minor glitch is that in Case, Curwen refers to seeing Yog-Sothoth's face, whereas in Dunwich, Yog-Sothoth and the Old Ones are supposed to be invisible. Of course, you can assume that Curwen used the powder of Ibn Ghazi to temporarily make Yog-Sothoth visible. But it seems likely that, at the time he wrote Case, Lovecraft simply hadn't yet decided that Yog-Sothoth is normally invisible.

Yog-Sothoth, 'Umr at-Tawil, and the Ancient Ones

The final major appearance of Yog-Sothoth is in Gates [], which Lovecraft revised from a draft by E. Hoffman Price. A brief resumé of the plot may prove useful here, even if you have read the story before. Randolph Carter begins by seeking "the enchanted regions of his boyhood dreams." He uses the mystic Silver Key to pass the First Gate to an extension of earth that exists outside of time. There he witnesses "a cloudy pageantry of shapes and scenes which he somehow linked with earth’s primal, aeon-forgotten past." This vision piques his curiosity so that he desires something more than simply to return to his childhood dreams.

At this juncture he meets the guide 'Umr at-Tawil, leader of a small group of cloaked beings called the Ancient Ones. Later we learn that these are manifestations of Yog-Sothoth. 'Umr at-Tawil offers to help Carter to pass through the Ultimate Gate, then performs a ritual and chants the Ancient Ones "into a new and peculiar kind of sleep, in order that their dreams might open the Ultimate Gate to which the Silver Key was a passport." Carter passes the Ultimate Gate and meets an awesome cosmic being:

It was an All-in-One and One-in-All of limitless being and self—not merely a thing of one Space-Time continuum, but allied to the ultimate animating essence of existence’s whole unbounded sweep—the last, utter sweep which has no confines and which outreaches fancy and mathematics alike. It was perhaps that which certain secret cults of earth have whispered of as YOG-SOTHOTH, and which has been a deity under other names; that which the crustaceans of Yuggoth worship as the Beyond-One, and which the vaporous brains of the spiral nebulae know by an untranslatable Sign—yet in a flash the Carter-facet realised how slight and fractional all these conceptions are.

Yog-Sothoth offers to show Carter "the Ultimate Mystery, to look on which is to blast a feeble spirit." He explains that

The world of men and of the gods of men is merely an infinitesimal phase of an infinitesimal thing... Though men hail it as reality and brand thoughts of its many-dimensioned original as unreality, it is in truth the very opposite. That which we call substance and reality is shadow and illusion, and that which we call shadow and illusion is substance and reality.

All beings in our universe are simply cross-sections, taken at various angles, of a number of higher dimensional archetypes.

The archetypes...are the people of the ultimate abyss—formless, ineffable, and guessed at only by rare dreamers on the low-dimensioned worlds. Chief among such was this informing BEING [Yog-Sothoth] itself . . . which indeed was Carter’s own archetype. The glutless zeal of Carter and all his forbears for forbidden cosmic secrets was a natural result of derivation from the SUPREME ARCHETYPE. On every world all great wizards, all great thinkers, all great artists, are facets of IT.

At this point, Randolph Carter's quest takes a tragic turn, one that raises many questions. He asks to experience "a dim, fantastic world whose five multi-coloured suns, alien constellations, dizzy black crags, clawed, tapir-snouted denizens, bizarre metal towers, unexplained tunnels, and cryptical floating cylinders had intruded again and again upon his slumbers."

The PRESENCE warned him to be sure of his symbols if he wished ever to return from the remote and alien world he had chosen, and he radiated back an impatient affirmation; confident that the Silver Key, which he felt was with him and which he knew had tilted both world and personal planes in throwing him back to 1883, contained those symbols which were meant. And now the BEING, grasping his impatience, signified Its readiness to accomplish the monstrous precipitation.

Carter gets stuck in the mind and body of the wizard Zkauba on the planet Yaddith. The remainder of the story concerns his efforts to return to earth, regain his original human form, and claim control of his estate.

The story resembles earlier works in the Randolph Carter series in some ways. As usual, Carter is on a quest to regain childhood fancies that he has lost. However, in other respects the story stands out as a major anomaly in Lovecraft's work. In the first place, Carter's bête noire from Kadath, Nyarlathotep, makes no appearance, nor is there any mention of Azathoth or the Other Gods. Has Nyarlathotep somehow lost interest in Carter? Perhaps his earlier attempt to feed Carter to Azathoth was opportunistic, or possibly intended as a punishment for Carter's attempt to visit the fabulous sunset city where the Great Ones have taken up residence.

Further, the concept of Yog-Sothoth in Gates seems quite different from the version of him in Dunwich. True, Yog-Sothoth continues to be associated with gateways between dimensions. But in Gates, Yog-Sothoth doesn't express any interest in helping the Old Ones to return to earth. Instead, he helps a human to leave earth and experience higher realities.

Regarding Yog-Sothoth's manifestations, 'Umr at-Tawil and the Ancient Ones, Carter decides that their bad reputations are undeserved:

There was no horror or malignity in what ['Umr at-Tawil] radiated, and Carter wondered for a moment whether the mad Arab’s terrific blasphemous hints, and extracts from the Book of Thoth, might not have come from envy and a baffled wish to do what was now about to be done.

Damnation, [Cater] reflected, is but a word bandied about by those whose blindness leads them to condemn all who can see, even with a single eye. He wondered at the vast conceit of those who had babbled of the malignant Ancient Ones, as if They could pause from their everlasting dreams to wreak a wrath upon mankind. As well, he thought, might a mammoth pause to visit frantic vengeance on an angleworm.

Yog-Sothoth expresses approval and encouragement for Carter's quest:

“What you wish, I have found good; and I am ready to grant that which I have granted eleven times only to beings of your planet—five times only to those you call men, or those resembling them. I am ready to shew you the Ultimate Mystery, to look on which is to blast a feeble spirit. Yet before you gaze full at that last and first of secrets you may still wield a free choice, and return if you will through the two Gates with the Veil still unrent before your eyes.”

Of course, Nyarlathotep also made a pretense of being encouraging.

So, Randolph Carter, in the name of the Other Gods I spare you and charge you to serve my will. I charge you to seek that sunset city which is yours, and to send thence the drowsy truant gods for whom the dream-world waits.

...I myself harboured no wish to shatter you, and would indeed have helped you hither long ago had I not been elsewhere busy, and certain that you would yourself find the way. [Kadath]

Possibly Yog-Sothoth, like Nyarlathotep, is acting as a trickster. But if so, it's hard to fathom what his goal is. He doesn't send Carter to be gobbled by Azathoth, nor to any other ultimate fate. He simply fulfills Carter's wish to experience life as the wizard Zkauba on the planet Yaddith. Did Yog-Sothoth realize that Carter would get stuck there? Carter doesn't think so:

The now inaccessible BEING of the abyss had warned him to be sure of his symbols, and had doubtless thought he lacked nothing. [Gates]

Yet, it is hard to believe that Yog-Sothoth, from his standpoint outside of time, would not know that Carter was about to make a horrible mistake.

Another question is whether the story expresses E. Hoffman's Price viewpoint more than that of Lovecraft himself. Fortunately, Price's original draft of the story, "The Lord of Illusion," has been published. We find from it that Price originated almost all of the storyline, as well as the cosmology in the story, involving the discovery that we are each just cross-sections of timeless archetypal beings. Price supplies us with 'Umr at-Tawil, the Ancient Ones, and the forboding quote about 'Umr at-Tawil from the Necronomicon. However, Price does not identify the Presence beyond the Ultimate Gate with Yog-Sothoth. It is Lovecraft himself who takes that step in his revision of the story.

Lovecraft sometimes rewrote the work of his paying revision clients in a very thorough and extreme way. I'm not sure whether he would have felt the same liberty when revising a work by a friend and correspondent. But I think there are a couple of other reasons that Lovecraft might have felt inclined to retain most of Price's cosmology in the story. Consider the summary by one of the characters in the story:

“This,” said one of those assembled in a certain house in New Orleans, “is plausible to a degree, despite the terrifically incomprehensible be-scramblement of time and space and personality, and the blasphemous reduction of God to a mathematical formula, and time to a fanciful expression, and change to a delusion, and all reality to the nothingness of a geometrical plane utterly lacking in substance...”

—E. Hoffmann Price, "The Lord of Illusion"[fn4]

These concepts would not be out-of-place in a Lovecraftian tale of cosmic horror. In the original draft, Price also devotes some space to mocking conventional religions, and specifically Christianity. Lovecraft excised these passages, perhaps because they are distracting and unnecessary, or because he liked to mock religion in a more indirect way. But they are further evidence of some overlap between Price's and Lovecraft's world-views.

In the end, Yog-Sothoth remains beyond Carter's comprehension. The voice of the Presence that Carter hears is the result of his own feeble attempt to make sense of a reality that is far above his level. Faced with a revelation of the ultimate nature of reality, Carter does not ask to ascend to Yog-Sothoth's level and experience the world of infinite dimensions outside of time. Instead, he wants to explore other limited cross-sections of that ultimate reality:

Without definite intention he was asking the PRESENCE for access to a dim, fantastic world whose five multi-coloured suns, alien constellations, dizzy black crags, clawed, tapir-snouted denizens, bizarre metal towers, unexplained tunnels, and cryptical floating cylinders had intruded again and again upon his slumbers. That world, he felt vaguely, was in all the conceivable cosmos the one most freely in touch with others; and he longed to explore the vistas whose beginnings he had glimpsed, and to embark through space to those still remoter worlds with which the clawed, snouted denizens trafficked. [Gates]

Even with this relatively limited goal in mind, Carter is swiftly undone by his overconfidence. Yog-Sothoth does not need to be malignant in order to be dangerous. He simply represents a reality that mortals cannot experience safely, or while remaining sane.

Another point to remember is that Lovecraft repeatedly toys with radical changes of perspective in his later stories, beginning with the narrator's ultimate embrace of his fishy fate in Innsmouth. The jump from presenting Yog-Sothoth as an apocalyptic horror in Dunwich to a benign guru in Gates helps to underline one of Lovecraft's later themes. The point is that the views and values of other species are ultimately no more or less valid than our own, parochial human viewpoints.

Great, Old, Ancient, and Other Ones

As we have seen, several of Lovecraft's stories refer to groups of god-like, alien beings that are not described in detail: the Other Gods/Ultimate Gods of the dreamlands stories such as Kadath, the Great Old Ones in Call, the Old Ones in Dunwich, and the Ancient Ones in Gates. The similarities make it tempting to conflate these groups. Unfortunately, Lovecraft's family tree of the gods sheds no light on the subject; it does not list any of these groups, perhaps because the chart is focused on the deities who are ancestors of H. P. Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith [Family]. But on examining the individual stories, the details seem to imply that Lovecraft regarded these groups as separate.

Old Ones and Great Old Ones

Are the Old Ones in Dunwich the same as the Great Old Ones from Call? There is some resemblance, aside from the nearly identical names. Like the Old Ones, the Great Old Ones are stuck somewhere, and they want to return. The Great Old Ones were imprisoned by Cthulhu to protect them while "the stars are wrong." Cthulhu and the Great Old Ones have to wait until "the stars are right" before their devotees can safely free them. By contrast, in Dunwich, we are told only that the Old Ones plan to take earth back to "some other plane or phase of entity" from which it fell long ago.

Like the Old Ones, there is also something dimensionally odd about Cthulhu; in describing his dream of R'lyeh, the artist Wilcox described "the damp Cyclopean city of slimy green stone—whose geometry, he oddly said, was all wrong..." Similarly, the sailors who found risen R'lyeh "could not be sure that the sea and the ground were horizontal, hence the relative position of everything else seemed phantasmally variable." [Call]

Unlike the Old Ones, Cthulhu is visible; he was seen by the crew of the Alert. Further, there are stone carvings of Cthulhu. And when the Great Old Ones came from the stars, they "brought Their images with Them." [Call]