|

The Descent of Robert Olmstead |

I never heard of Innsmouth till the day before I saw it for the first and—so far—last time. I was celebrating my coming of age by a tour of New England—sightseeing, antiquarian, and genealogical...

Tainted ancestry is one of the recurrent themes in Lovecraft's fiction, showing up in Arthur Jermyn, The Lurking Fear, The Rats in the Walls, The Festival, Pickman's Model, The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, The Dunwich Horror, and most famously, The Shadow Over Innsmouth. The psychological force of this motif might derive from his own family history; both his parents were eventually confined to sanitariums, in his father's case because of syphilis, though Lovecraft probably never knew the cause. Or the motif might derive from his view of humanity as essentially beastial, with only a thin veneer of civilisation that is all too easily swept aside. Further fuel many have come from his belief that each civilisation inevitably succumbs to decay, and that modern Western civilisation has entered an irreversible decline. For a discussion of these factors in Lovecraft's thought and work, see S. T. Joshi's work H. P. Lovecraft: The Decline of the West.[1]

In "The Shadow Over Innsmouth," the "tainted ancestry" theme converges with a number of Lovecraft's other phobias: his racial animosity, his loathing of all fish and sea food, and his sense that humanity and human values are transient and insignificant in the larger cosmos. Since few of us share Lovecraft's exact combination of anxieties, it is unlikely that the scenario of "The Shadow Over Innsmouth" has ever frightened a reader nearly as much as it frightened him. But it is remarkable that he was able to express so many types of alienation in this single story.

The final, ultimate horror that emerges in "Innsmouth" is the the narrator's discovery that he is an imposter: not at all an exemplar of the upper class, genteel, white Anglo-Saxon culture that he identifies with. And his downfall is nothing of his own doing, but the result of one flaw in his ancestry: a single great-great-grandmother who was not human, but rather a member of another species that enjoyed humans as sacrifices and also "hankered arter mixin’" with us.

Of course, a strong emotional impetus is not enough to make a great story. The lasting impact of "Innsmouth" is possible because of how carefully Lovecraft developed it; not just in terms of an evocative writing style, but also a carefully worked out geography and history. Because Lovecraft developed these details in advance, he can disclose them in the story in a layered way, through a series of informants who can fill in more and more of the gaps in the narrative.

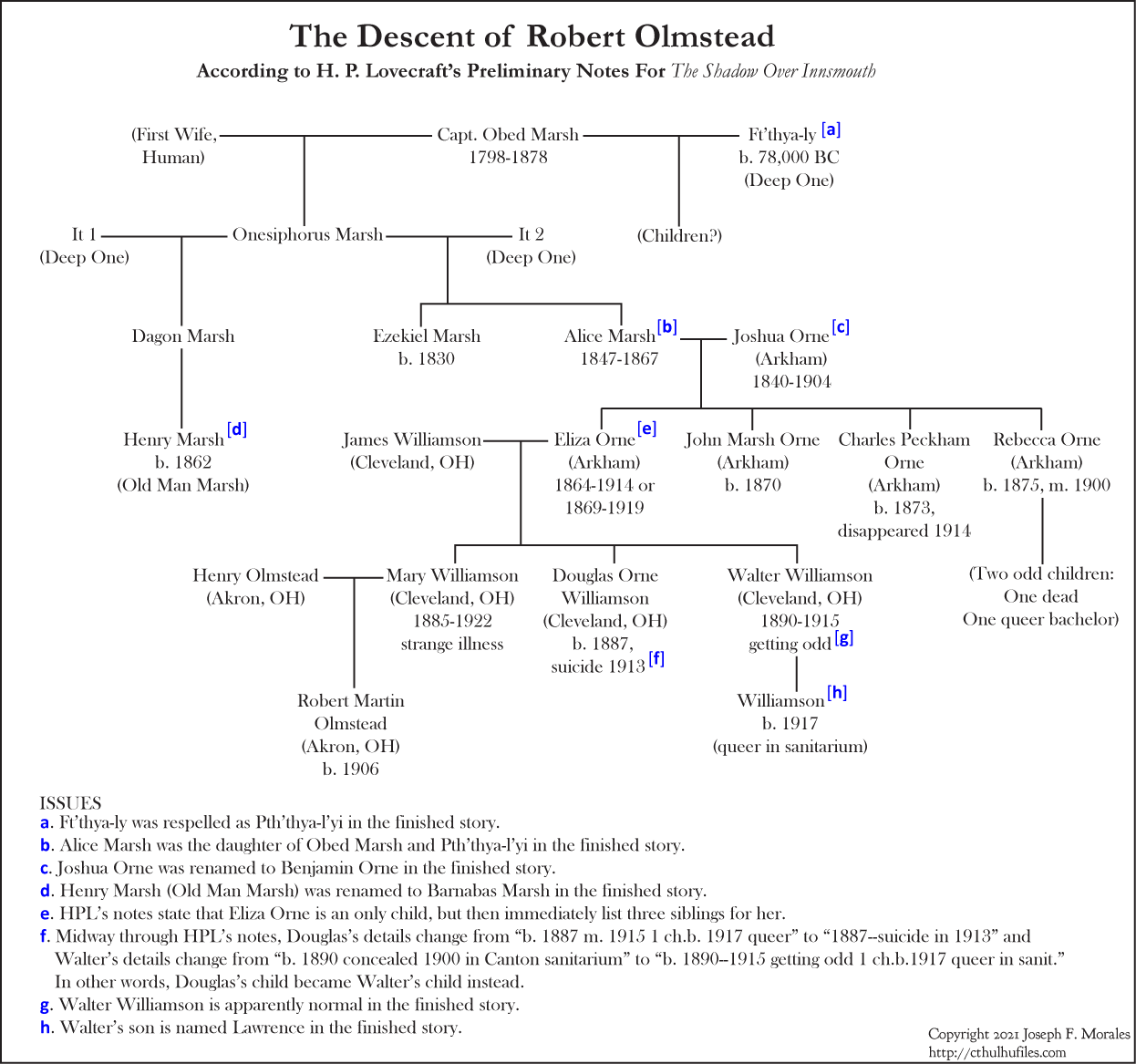

As part of this preparation, Lovecraft's provided a sketch of the narrator's ancestory in his notes for the story.[2] These notes identify the narrator as Robert Olmstead. However, it's good to remember that these notes reflect a preliminary phase in his planning for the story. The notes have internal inconsistencies, and also contradict the published story in several ways. Following is a redrawn version of the genealogy that Lovecraft sketched out for Robert Olmstead in his notes, together with a list of various issues in this account.

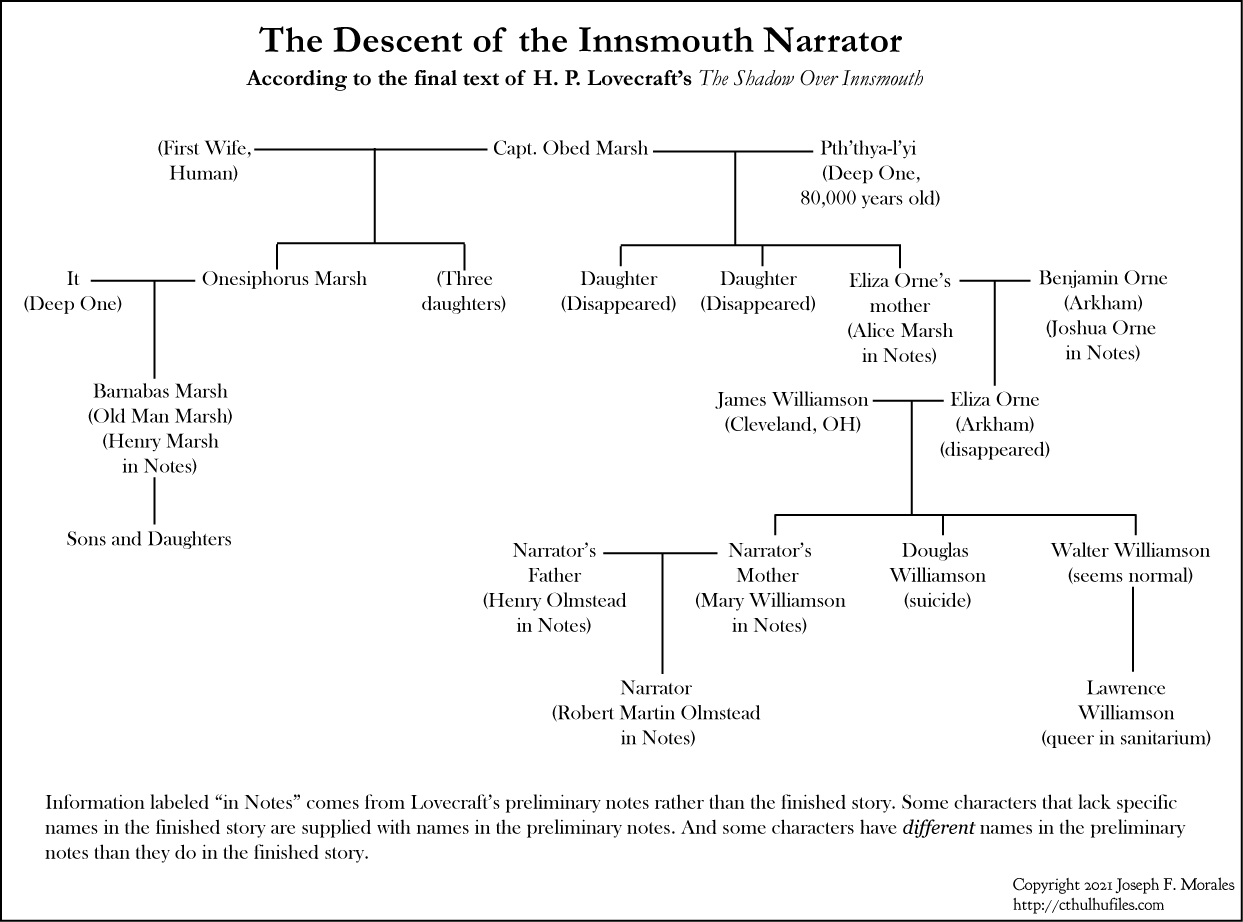

For the final story, Lovecraft may have felt that this level of detail would be overwhelming to the reader. Accordingly, some of the people listed above are not mentioned in the finished tale. More importantly, Lovecraft decided to make the narrator a direct descendant of Capt. Obed Marsh, who first brought the Deep Ones to Innsmouth, and Marsh's consort, the 80,000 year old Pth'thya-l'yi. This is much more satisfactory than the original genealogy, which did not mention any offspring for Obed Marsh and Pth'thya-l'yi, and in which the narrator's taint enters the picture more indirectly, through Obed's son Onesiphorus and one of his Deep One consorts (whom Lovecraft charmingly refers to as "It" or "Thing").

These genealogies suggest a number of interesting, and rather open-ended, reflections.

One of the big leaps in the story is the assumption that two species could breed and have viable offspring.[3] Although this is not entirely unheard of —"In fact it has been estimated that 88 per cent of all fish species could hybridise with at least one other, given the opportunity. The same may be true of 55 per cent of all mammals."[4] — it would be extraordinary for two species as different as humanity and the Deep Ones to be able to have viable offspring. It's one of the instances in Lovecraft's stories where his desire for a certain type of horror scenario seems to override his respect for modern science. For all the talk about his later stories becoming more like "science-fiction," the science was always used as mere window-dressing or rationalization for his horror scenarios, rather than as the starting point for science-inspired speculation. Asimov he was not. The only rationale that Lovecraft provides in this story is the rather weak "Seems that human folks has got a kind o’ relation to sech water-beasts—that everything alive come aout o’ the water onct, an’ only needs a little change to go back agin." Really? It's not like humans can have children with sharks, dolphins, or sea lions. Lovecraft keeps the mechanism vague, because it is fundamentally not of interest to him.

However, suppose we've granted the basic premise. From the standpoint of biology, it would seem that the Deep Ones must have a genetic code that follows similar principles as other earth life, or there would be no possibility at all of them breeding with us. Although the DNA molecule was not discovered in Lovecraft's time, the role of Mendelian genetics in evolution was understood by the 1920's.[5] Yet it's not clear that Lovecraft thought through the Innsmouth taint in terms of Mendelian genetics. His character Zadok summarizes the process as follows:

Wal, Sir, it seems by the time Obed knowed them islanders they was all full o’ fish blood from them deep-water things. When they got old an’ begun to shew it, they was kep’ hid until they felt like takin’ to the water an’ quittin’ the place. Some was more teched than others, an’ some never did change quite enough to take to the water; but mostly they turned aout jest the way them things said. Them as was born more like the things changed arly, but them as was nearly human sometimes stayed on the island till they was past seventy, though they’d usually go daown under fer trial trips afore that.

Interestingly, the only mentions of Deep One/human liaisons, in both the finished story and the preliminary notes, are all between female Deep Ones and male humans. It is difficult to say whether Lovecraft intended that male Deep Ones can also breed with female humans.

The narrator's taint descended entirely through the female line, from his great-great-grandmother Pth'thya-l'yi, to his great grandmother Alice Marsh, grandmother Eliza Orne, and mother Mary Williamson. However, the taint can also pass through the male line. Lawrence Williamson apparently inherited the taint through the male line, from his father Walter, who did not show any sign of the taint. For the taint to skip a generation might seem to imply that it is a genetically recessive trait, but actually things are not that simple. There is no mention that Lawrence's mother had any Deep One ancestry, and given that the family lived in Ohio, it seems unlikely anyway. So it doesn't look like Lawrence's mother contributed any second instance of a recessive "Deep One" gene.

It's also interesting that the taint doesn't get diluted over the course of generations. A single Deep One great-great-grandparent was sufficient to seal the narrator's fate. But if the trait is dominant rather than recessive, then why does it sometimes skip generations? Nowadays we know that many genes can modify each others' effects, and epigentic factors can also affect how genes are expressed. But in the story, the concept probably results more from what Joshi called Lovecraft's "utter decimation of human self-importance by the attribution of a grotesque or contemptible origin of our species."[6] It's easy for humans to revert to being abhorrent, fishy things because that's our true, original nature.

Another intriguing question is why the town of Innsmouth got so run-down and decayed after generations of dealing with the Deep Ones. After all, the bargain brought good fishing and an ongoing supply of gold to the town. One reason, provided by the narrator, is that "fishing paid less and less as the price of the commodity fell and large-scale corporations offered competition". Additionally, it is possible that the Deep Ones supplied only relatively small numbers of gold items, and the Marsh family also considered it wise to keep the gold trade on a small scale so as to avoid attracting undue attention. Then again, as more and more of the Innsmouth populace became more obviously tainted, it became necessary for many to live in concealment, pending their full transition to water life. Such beings would not be able to go outside and get jobs to contribute to the local economy. Most importantly, for the Innsmouth people, human life became a mere prelude to their immortal life beneath the waves, so there was little reason to aspire much to human goods.

For the narrator, this lesson comes belatedly. Even after his trauma in Innsmouth, he goes back to college and plans to pursue a normal human life, a life that turns out to be wholly illusory. Instead, his unknown past becomes the dictator of his future. Created by random events that predated him, he has no ability to choose his own destiny. He is the quintessential Lovecraftian protagonist, cursed to learn things that destroy his worldview, and too weak even to use his automatic pistol to take his own life. The descent from his ancestors is also his own descent to the watery abyss. The inside becomes the outside, and the ocean hidden within him becomes the ocean that submerges him at last.

[1] Joshi, S. T. H. P. Lovecraft: The Decline of the West. Wildside Press LLC. Kindle Edition.

[2] Lovecraft, Howard P., collected by Derleth, August. Something About Cats and Other Pieces. New York, 1971: Books for Libraries Press. (Reprint of the original 1949 Arkham House edition.)

[3] The other big leap is the notion that the narrator's wild story would have been taken seriously by the government authorities. "Let me see, you say there are fish people in a tiny, decrepit New England seaport who are planning to take over the earth? Golly, that sounds serious. Let's send in the military before it's too late!"

[4] Marshall, Michael. "A Long-Busted Myth: It's Not True That Animals Belonging To Different Species Can Never Interbreed." Forbes, published Aug 28, 2018,11:41am EDT, https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelmarshalleurope/2018/08/28/a-long-busted-myth-its-not-true-that-animals-belonging-to-different-species-can-never-interbreed/?sh=199c2d7a3e65, retrieved 6/27/2021.

[5] Charlesworth, Brian and Charlesworth, Deborah. "Darwin and Genetics." Genetics, November 1, 2009, vol. 183, no. 3, 757-766; https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.109.109991, retrieved 6/27/2021.

[6] Joshi, S. T. H. P. Lovecraft: The Decline of the West. Wildside Press LLC. Kindle Edition.

Return to Cthulhu Files home page

Send comments to jfm.baharna@gmail.com.

© Copyright 2021 by Joseph Morales.